Why you should be paying more attention to the field of microbiology – it affects you more than you know.

When I attended the Carnegie Mellon Rustbelt Microbiome Conference, I left with one core piece of knowledge: I should be eating more fiber.

The conference takes place in Pittsburgh, PA, and is a place for microbiologists to present their latest research, network with one another, and uplift undergraduate voices in the field. As I watched each person present, I paid close attention to the ways these researchers used signs and symbols, elements of storytelling, and rhetor-audience connection in order to make their findings accessible to people who aren’t as well-versed in their particular area of research.

Because of these translational tools and the gift of asking questions, I was able learn more about these findings and their implications – many of which absolutely blew my mind.

One of the most striking studies I learned about was conducted by the Bailey Lab at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio – the research was about how prenatal stress in the mother can lead to microbiome-related issues in offspring. I had so many questions: How can something psychological like stress alter someone’s physical microbiome? How wide-reaching are the effects of the mother’s stress on the infant? What are the implications of this newfound information?

Luckily, I was able to chat with one of the microbiologists behind this research and get these questions answered. Audrey Duff is a postdoctoral researcher in the Bailey Lab, which primarily focuses on the role of the microbiome in how stress and disease impact behavior.

Microbiome and You

First off, what is a microbiome? You have microbiome everywhere – your skin, nose, mouth, respiratory system, and especially in your gut. It is essentially a team of microscopic organisms that helps you with things like digestion, absorbing nutrients, and protecting you from harmful bacteria. The many different microbes that make up this team are determined by factors such as diet, exercise, stress, environment, and even whether you were born vaginally or through a C-section.

What does it do?

The microbiome can…

- Produce bacterial metabolites: These are substances created as a result of the microbiome’s bacteria breaking down or fermenting things in our body, particularly the food we eat. It aids in digestion, nutrient absorption, and supports our immune system.

- Effect neurotransmitters: These are chemicals that carry messages through your body and brain – like dopamine, oxytocin, and more.

- Produce bacterial antigens: This is the part of the bacteria that flags it as foreign, meaning it needs to be checked out by the immune system. This can trigger an immune response where your body begins to fight off a potential threat.

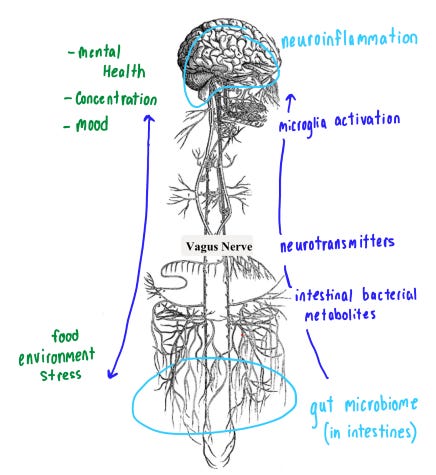

If these processes get disturbed, it can lead to activation of microglia cells, the brain’s primary immune cell: they clean out ‘dead’ cells in the brain and protect it from bacteria or viruses. Activating the microglia cells sets off a sort of alarm that causes the production of cytokines (the immune systems communicators) that can trigger neuroinflammation, which happens when the brain is trying to fight off injury and infection. Sometimes, it is good for us and helps us heal, but long-term it can lead to negative mental & cognitive effects. It can make you feel fatigued, give you headaches, and other uncomfortable symptoms. Physically, your gut and brain are primarily connected through the Vagus nerve, or the gut-brain axis. Let me draw this out for clarity:

Audrey’s Research

After learning this foundational information about how the microbiome affects so many of the body’s systems, I then got the chance to dive deeper into a specific area of this research that broadens the scope of these effects. Audrey’s research revolves around how stress in a pregnant mother can affect the health of the child, and what role the microbiome plays in that connection.

Previously, we knew that children exposed to prenatal stress have a higher risk of getting respiratory infections. A study from 2011 found that children exposed prenatally to stress had a 25% increased risk of being hospitalized with a severe infectious disease compared to non-prenatally stressed children. (Similar studies can be found here and here).

Audrey’s research looks at this phenomenon through the lens of the microbiome – how can the microbiome act as a mediator in the communication between mother and child? Are the abnormalities in the microbiome associated with prenatal stress the reason the children are more susceptible to sicknesses?

By studying mice, she found that prenatally stressed offspring exhibit increased expression of proinflammatory and interferon genes in the intestine and lungs – essentially, that means that the body is boosting its defense mechanisms due to the stress. Similarly to how processes in the microbiome can affect neuroinflammation, it also can inflame our immune system in the same way. Again, this bodily defense could be beneficial, but too much could be harmful.

So, in children whose mothers experienced a lot of stress during pregnancy, there is proven to be disturbances in the child’s microbiome that can lead to a lessened ability to fight sicknesses, specifically respiratory infections.

To me, this research was so striking because it shows how stress can affect not only our own body in so many ways, but also is hereditary and long lasting – one’s own mental state can affect their child’s health post-birth. After researching the biology behind how your gut health can affect mental health in conjunction with Audrey’s research about the physical effects of stress, this gives the issue of mental health a much wider scope.

What do I make of this?

After learning about the direct connection between your gut and your brain/immune system, it gave me a larger understanding of how all the processes of your body are connected. I started to gain insight into why the times in my life when I am mentally sharp stand in stark contrast to the times when I am more lethargic, don’t feel like cooking healthy meals, and can’t focus.

In fact, many of the studies in the Microbiome Conference mentioned this gut-brain axis, which is what made me so curious about it in the first place. Many studies emphasized the importance of a high-fiber diet for keeping the gut microbiome healthy. Eating lots of grains, fruits, and vegetables can help to make this system thrive.

I had heard of this before – in fact, gut health is a bit of a viral moment right now on social media. I think there are some dangers that can arise when medical information becomes trendified; for instance, people may overestimate the real impact of certain issues simply because they hear them repeatedly online. Much of the gut health information in the media is delivered to us in a way that has been hijacked by an influencer trying to sell us a certain product or new diet fad. I believed in gut health before, but also subconsciously figured that much of its importance can be attributed to people online trying to push certain body trends or sell me something.

Attending the microbiome conference completely reworked that narrative for me. Paying attention to real scientists and understanding the mechanisms behind this research – how these aspects of our health are connected, and why it is important – is the best practice in interacting with this information because it can increase understanding and self-efficacy. Engaging with professional scholarship and research behind a topic can bring a lot of clarity into the information that we may see online.

Our microbiome and bodily systems are no different than everything else that makes us human – we are sensitive, complex, and meant to be handled with care. Taking care of yourself on all fronts: regulating stress, eating healthily, and resting are all scientifically proven to help your mind and body in many ways. Remembering the basics and keeping self-care simple is the best way to avoid getting overwhelmed by the large amounts of ever-emerging new health information.

Thank you to microbiologist Audrey Duff for expanding on this research about the gut-brain and gut-lung axis! Learning this information in the context of mother-infant communication and effect on respiratory health was super interesting and speaks to the impressively large impact of microbial research.

So, even though this research can be quite complicated, I hope you take one simple piece of information away from this… don’t stress yourself out, it’s not good for you! (And don’t forget to eat your fiber, of course)

Leave a comment