Microbiologist Bailey Smith on Interbacterial Communication

Recent research at Carnegie Mellon University’s Hiller Lab could significantly change and enhance our understanding of disease. (Read the lab report here!)

Streptococcus pneumoniae is a bacterium that primarily sits in the upper part of your throat, behind your nose. It’s very common and can be spread in the same way as many other sicknesses: kissing, touching a public door handle, or being in the splash zone of someone’s sneeze. The good news is that this bacterium isn’t all evil. In fact, when just sitting in the back of your nose, it can be very well behaved – it can’t even get you sick unless it travels down your throat and into your respiratory system. However, if the bacteria decide to flip that switch, you may be at risk of experiencing pneumonia, ear infection, sinus infection, or other illnesses.

This ‘decision’, the moment the bacteria begin to invade, is what Carnegie Mellon’s Hiller Lab focuses on in their research. Essentially, in order for bacteria to multiply or mobilize, they have to have some way of communicating with one another. The messages bacteria send help their species survive in their environment; for example, in Streptococcus pneumoniae, they share messages about fighting off the immune system and creating a community called a biofilm, which is a sticky, thin slime that the bacteria can create to stick together and defend themselves.

The Hiller Lab focuses on deciphering bacterial communication – while we can infer the general idea of their messages by studying their actions, the biggest mystery lies in understanding how these messages are delivered. Furthermore, if we can figure out the mechanics behind how bacteria communicate, how could we potentially interrupt these calls to action? Could we find a way to send out a message that tells the bacteria to behave? This research is a step towards finding new ways to fight diseases by cutting them off at the source.

Cell’s Dialogue and Action

Previously, we knew that Streptococcus pneumoniae could spread messages across its colony via Quorum Sensing. This is when bacteria releases chemicals called peptides that spread an action message to a large group instantaneously – think of this method as mass communication that informs the bacteria and helps them to coordinate. Then, for Streptococcus pneumoniae, quorum sensing can even lead to changes in the transfer of genetic material:

- Vertical Gene Transfer: During this process, a cell replicates its DNA, and the two copies are distributed into daughter cells that have the exact same genetic makeup as the original. Over time, these generations can adapt and mutate depending on their environment.

- Horizontal Gene Transfer: This process involves transferring genes between cells that aren’t originally related through one of three mechanisms: uptake of free DNA from the environment (transformation – this one will be important later!), exchange through viruses that infect bacteria called bacteriophages (transduction), or direct transfer of DNA via a physical connection called a pilus (conjugation).

Within the second category, the Hiller Lab discovered an entirely new method of gene transfer—one that reshapes our understanding of the changes occurring within cell colonies. I got the chance to speak with a microbiologist on the team, Bailey Smith, to learn more about this discovery and what it could mean in terms of both foundational field knowledge and potential disease treatments.

Bailey’s Research

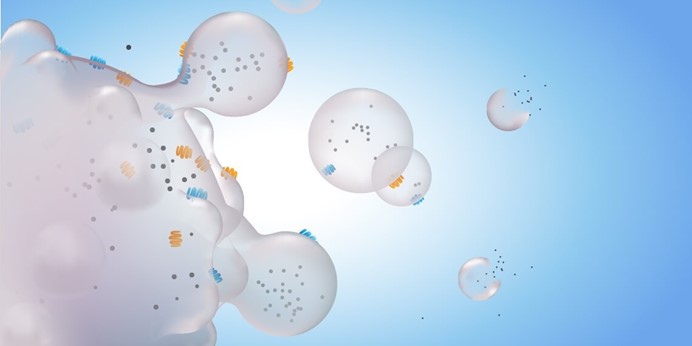

When thinking about a photo of a cell, like one you may see in biology class, it is usually portrayed as having a rigid, fixed edge. But cells are much more malleable than that. Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are a ‘blub’ that comes off the original cell when its exterior gets bent to an extreme:

By first proving that DNA is on the outer surface of EVs, then studying the genetic makeup of the EVs compared to its original cell, the lab was able to prove that the EVs carry messages which other cells can take up through transformation. Previously, transformation was understood only in the context of free-floating DNA: a cell absorbs DNA from a lysed (dead) cell by pulling it through surface pores, integrates the DNA into its genome, and expresses new traits such as antibiotic resistance.

The unique thing about DNA exchange through extracellular vesicles is the unprecedented amount of information they can carry. Bailey described it to me by saying, “Before, if communication was like a sentence, extracellular vesicles are like a paragraph.”

There are two main groups of bacteria: Gram-positive, which has a thick cell wall, and Gram-negative, which has a thin wall and extra membrane layer. Previously, EVs weren’t commonly viewed as a delivery system for Gram-positive bacterial colonies because the thick border was thought to inhibit their formation and release. Yet, this research found that EVs act as a mediator for change in colonies of Streptococcus pneumoniae, a Gram-positive bacterium. This is where the perspective-shift takes place.

By casting the foundations of this research, the Hiller Lab created a new platform to build upon for understanding how information delivery takes place between cells. Then, through investigating the cell’s language, we may be able to pinpoint the switch that takes place when the colony turns from harmless commensal bacteria into a full-blown pathogen.

Personally, what drew me to this research specifically was the way that we characterize cells; it is an example of how we, almost reflexively, use human-like frameworks to guide our understanding and research of non-human things. For example, we use ideas about identity, hierarchy, and governance, which only truly exist in human constructs, to guide research about animal groups in the wild. We even design technology based on human cognition and physicality. It is interesting how all fields are connected through one common factor: the humans who study them.

Anyways, I was super excited to get the chance to further explore this research, so a big thank you to Bailey Smith from the Hiller Lab at Carnegie Mellon! This specific niche of microbiology now feels like a story that I’m following, and I’m just waiting for the next episode to be released. So, stay tuned to see where this research goes next!

Leave a comment