Getting speculative about AI and the future of the medical field

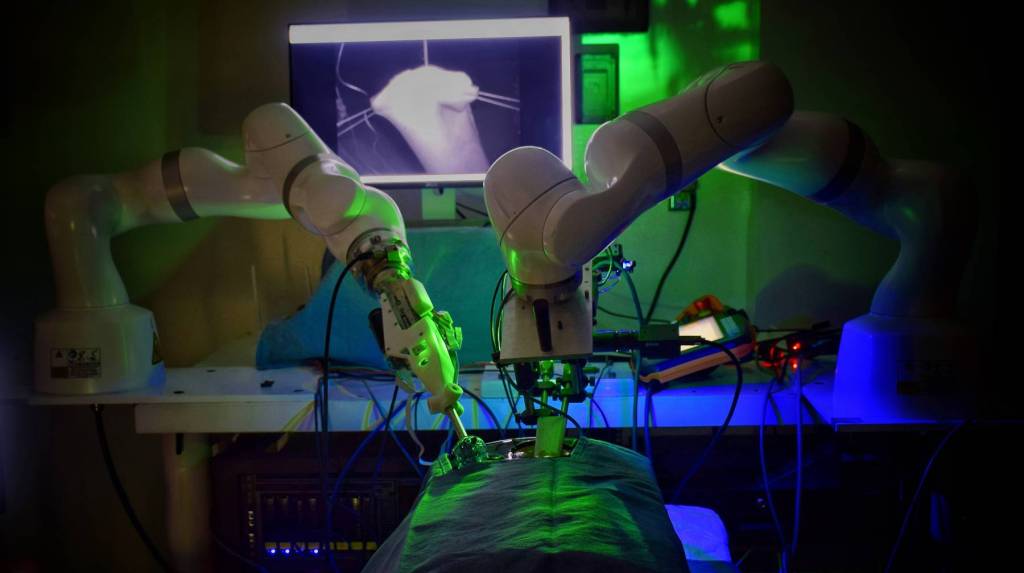

Imagine when you lie down on the surgical table, as you drift in an anesthesia-induced sleep, it is not humans that stand above you, but instead is a silver conglomeration of robotic arms ready to extend downward and perform your operation. The whirring of the machine is accompanied by the pedal-click of the surgeon, who sits across the room with their head enclosed in a VR console. This scenario is not fiction – it is our new reality with the popularization of surgical robots in the medical field.

The da Vinci Surgical System, developed by American biotechnology company Intuitive Surgical and launched in 1999, became the first robotic surgery device to receive FDA approval in 2000. Now widely adopted across the globe, it had been used in approximately 8.5 million procedures by 2021 and is employed in thousands of hospitals across 69 countries.

As the first surgical robot to achieve widespread clinical integration, the da Vinci paved the way for robotic-assisted surgery with its precision and its ability to enhance a surgeon’s physical abilities.

On the robot itself, each of its four arms are made of a series of hinges to facilitate dynamic movement, leading all the way down to centimeter-long clips that interact with the body and physically perform the operation. This part of the machine is only half of it: The other half is across the room, where the surgeon is sitting with their face enclosed in a large box, each finger and foot connected to the machine by straps and pedals. Each movement performed by the doctor correlates to a movement in one of da Vinci’s arms or clips, thus allowing for a completely human-controlled robotic surgery.

The system’s camera provides a 3D view of the surgical site with up to 10x magnification, giving surgeons an entirely new and immersive perspective. According to surgeons at Helena OB/GYN, a woman-focused healthcare facility in Helena, Montana, using the da Vinci is “like walking around inside the patient and being able to perform any type of major surgery through a laparoscope”

This futuristic technology has undeniably moved into the realm of post-modern. This device makes clear the reality that we have wandered far from the path of traditional surgical procedures and fully embraced technology as a mediator between physicians and patients

In exploring the use of da Vinci in pediatrics, Alejandro Garcia, the director of pediatric robotic surgery at Johns Hopkins University, explains, “The robotic platform has allowed us to consider minimally invasive surgery for very complex cases, such as on the pancreas and liver, that would not have been amenable to traditional laparoscopic surgery”

Though the idea of the surgeon not being at the surgical table is a weird and confusing concept, people who can get past it have found the results to be incomparable. On social media, people attest positively to the device: “I’ve had 2 endo surgeries, 1 done robotically then other manually and I preferred the robotic one“ says KoalaLuvs on Reddit in the thread r/endometriosis.

“I had surgery using a DaVinci machine. Saved my life and I only had three tiny scars. Amazing technology“ – CompoBeachGirl

The reviews of the machine online are overwhelmingly positive. But would you be able to overlook the idea of sitting under only a machine? What aspects of human-to-human care do we begin to see being put at stake as technology develops in the medical field?

What happens when the surgical robots not only infringe upon human physicality, but they begin to imitate human cognition and decision-making as well?

The Future & AI Integration

Meet STAR: The first ever fully autonomous surgical device. This technology was created by engineers at Johns Hopkins University in 2022 and is a machine-learning adaptation of the da Vinci. Essentially, it is moving and making decisions on its own, replacing the human driver in the Da Vinci with an AI system.

STAR uses machine learning to watch videos of a particular procedure, and then generates a suturing plan based on the tissue’s thickness and shape by drawing on insights from the videos it had processed. It combines aspects of deep learning and generative AI to create a plan and execute it with precision – it is even able to counter unexpected movements or changes in its original plan if necessary.

For example, in the clip on the left, STAR makes a mistake in tying the knot in the stitch but is easily able to recalibrate its plan and try again.

In testing the device, the machine completed the first ever laparoscopic surgery without human help where it successfully sewed together the intestine of a pig.

The system is currently undergoing pre-clinical studies and is expected to enter human testing by 2027.

In this intersection between the widely-used da Vinci and the currently developing AI-powered STAR, what unprecedented ethical issues are on the horizon? What issues are we seeing now, and how will they continue to develop?

Affordances of Tech-Forward Surgery

In terms of surgical medical care, AI being implemented in fashions similar to STAR could create more accessible surgeries – imagine a world where the time surgeries take is significantly reduced and the physical procedure itself is streamlined. With quicker turnover and fewer specialists required in the operating room, hospitals would have more available beds and lower surgical costs, ultimately making procedures less expensive for patients.

We’ve already seen glimpses of this cost-reducing, efficiency-enhancing trend in areas where AI has taken root in healthcare, like chatbot consultants and digital therapists, where access has expanded and prices have dropped drastically.

Sebastian A. Bernaschina Rivera, a resident at University of Miami Desai Sethi Urology Institute, says he plans to train on the da Vinci.

“From a user experience perspective, the da Vinci offers incredible precision, improved ergonomics, and a less physically demanding experience compared to traditional laparoscopy. This likely translates to more longevity in a surgeon’s career,” says Rivera.

Many of the affordances of AI surgery mirror the benefits of human-controlled surgical systems: enhanced precision, reduced strain on surgeons, and improved patient outcomes. But beyond that, AI has the potential to bridge geographic and economic gaps in healthcare access. In rural or under-resourced areas where specialist surgeons may be scarce, AI-assisted or autonomous surgical systems could help standardize high-quality care. Speculatively, we could see a world where the most skilled and specialized surgeons could encode their technique and it could be replicated on anyone, anywhere.

Possible Risks

The normalization of AI-powered surgical devices may change how we perceive surgery, making human-to-human care a luxury rather than the norm. As these technologies surpass human ability, their integration into medical practices could prioritize efficiency and profit over patient well-being and surgeon autonomy. In talking about the ethical implications of robotic surgery, the National Institute of Health suggests:

“In light of the high costs of devices’ maintenance and training, adopting institutions have a strong incentive to further a constant and broad use of [Robotic Assisted Surgery] and may incentivize or even pressure their employees to comply in order to ensure adequate monetary revenue”

The da Vinci and other surgical devices that are currently in use are undeniably ushering in some unprecedented ethical issues related to quality of care versus profit for the institution. How would AI being implemented into surgical care exacerbate these issues? We already are beginning to see the ways in which robotic surgery puts personalized, humanistic care at stake – will AI push these issues beyond return?

For example, if something goes wrong with an AI-powered surgery, who is responsible? Would it be the people who engineered the machine learning system, the surgeon who was performing in the videos it learned from, the mechanic who installed the machine or comes in for maintenance repairs, or maybe even an insurance company that wouldn’t offer coverage for a human surgery if, in the future, human care becomes a luxury?

Furthermore, future surgeons may only be trained to operate on robotic systems rather than perform procedures themselves, leading to a decline in hands-on skills and creative problem-solving. Overreliance on technology could result in a rigid medical system where doctors lack the adaptability to handle unexpected challenges. Ultimately, this paradigm shift into robotics risks diminishing the human element in medicine and losing traditional expertise.

The idea that we may essentially forget surgical skills over time may seem far out, but this reality is already taking place with the da Vinci device. Rivera notes, “We’re now seeing an entire generation of surgeons trained almost exclusively on this specific platform – some without confidence in performing laparoscopic or even open procedures.”

If surgeons are trained on this tech-forward technology, and institutions want to attract and retain surgeons, then hospitals purchase more robotic devices. This cycle that diminishes the need for traditional surgery has already begun – how will this same cycle repeat when AI-powered devices like STAR become the norm? I can’t help but imagine an industrialized, factory-like postmodern depiction of procedural medical care.

My Thoughts & Best Practices

When it comes to developing technologies, it is important to uplift the voices of those in interdisciplinary fields in the back-end engineering of these technologies. Think of this scenario in this way: Imagine you had a sociologist, IP lawyer, and environmentalist in the room where they coded ChatGPT. In a world where our backgrounds deeply affect our perspectives, having a variety of voices to shape the foundations of emerging tech could drastically shift outcomes. It ensures that questions of equity, sustainability, legality, and human impact are not just afterthoughts, but integral to the design process.

Another real-world example of this is digital interfaces not being accessible to many blind, dyslexic, hard-of-hearing, or even low-digital-literacy individuals like those in low-income communities who don’t often have exposure or access to technology. For example, in this article, I report on a solution where information about psychology, behavioral theory, and education are all used to combat these social barriers. Cristina Conati, a computer science professor at British Columbia University, engineered an AI system that uses eye tracking and detects a user’s level of digital literacy to make information on the screen easier to read – it can blur irrelevant information, simplify information, and visually adapt the individual user’s needs.

If AI surgical tools like STAR had interdisciplinary design teams – say, including bioethicists, disability advocates, and healthcare equity researchers – its development goals might shift. For example, in terms of the machine itself, instead of only optimizing for technical precision or cost-effectiveness, it could learn to prioritize personalized patient experience. One scenario where this might come into play is gender affirming care: with input from those in sociocultural fields/gender studies, a machine might be programmed to adjust incision types based on patients’ personal aesthetic goals and not just the “most efficient” method.

Furthermore, having anthropologists, sociologists, or other humanities fields at the back end of this technology to consider the patient’s first-hand experience would be very important: everything from consultation to the day of the procedure. One way that an interdisciplinary initiative could aid this process would be to employ medical narratives about individual patient experiences into certain areas of STEM education, ensuring that engineers understand the emotional and real-world implications of the products they create.

The role of a medical professional or medical product developer is deeply embedded in STEM education, where humanistic knowledge is taught as an afterthought or supplement to the main material. Furthermore, the socioeconomic barrier that exists to positions of medical power deepens divides that already exist in our society – those in positions with technological medical influence are more likely to have oppressive biases due to their position at the upper levels of our sociocultural hierarchy. A social justice lens would stand in stark contrast to device developers whose focus – and financial incentive – is on technological efficiency.

Where does the da Vinci fall on the ‘human experience’ scale? Where will STAR and similar AI devices fall? How can we implement humanitarian voices in robotic devices as they continue to develop technologically – infringing upon both a doctor’s physicality and cognition – to ensure that the medical field doesn’t become completely engulfed in STEM procedures and lose its communicative and care-based elements?

Technology doesn’t exist in a vacuum – so why should its creators?

Leave a comment